John Opera’s work combines a singular fascination with the visual properties and beauty of natural and scientific phenomena and a rigorous exploration of the techniques and processes by which photographs are made. For his Front Room project at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, he will present his recent Anthotype series of works related to photography’s experimental beginnings in the mid-nineteenth century. Opera uses colored solutions derived from various flower and fruit extracts that are light sensitive enough to create abstract images that are simultaneously pictorial and tactile. The “anthotype” process takes up to three weeks of exposure in direct sunlight to render an image and was quickly abandoned in the early development of photography when silver nitrate was discovered to have a much faster reaction time. Opera’s deliberate reconsideration of a photographic technique discontinued from the outset of the medium’s history not only reminds us of the vital necessity of experimentation in the visual arts but also extends and deepens his investigations into how photography both captures and incorporates natural processes and phenomena.

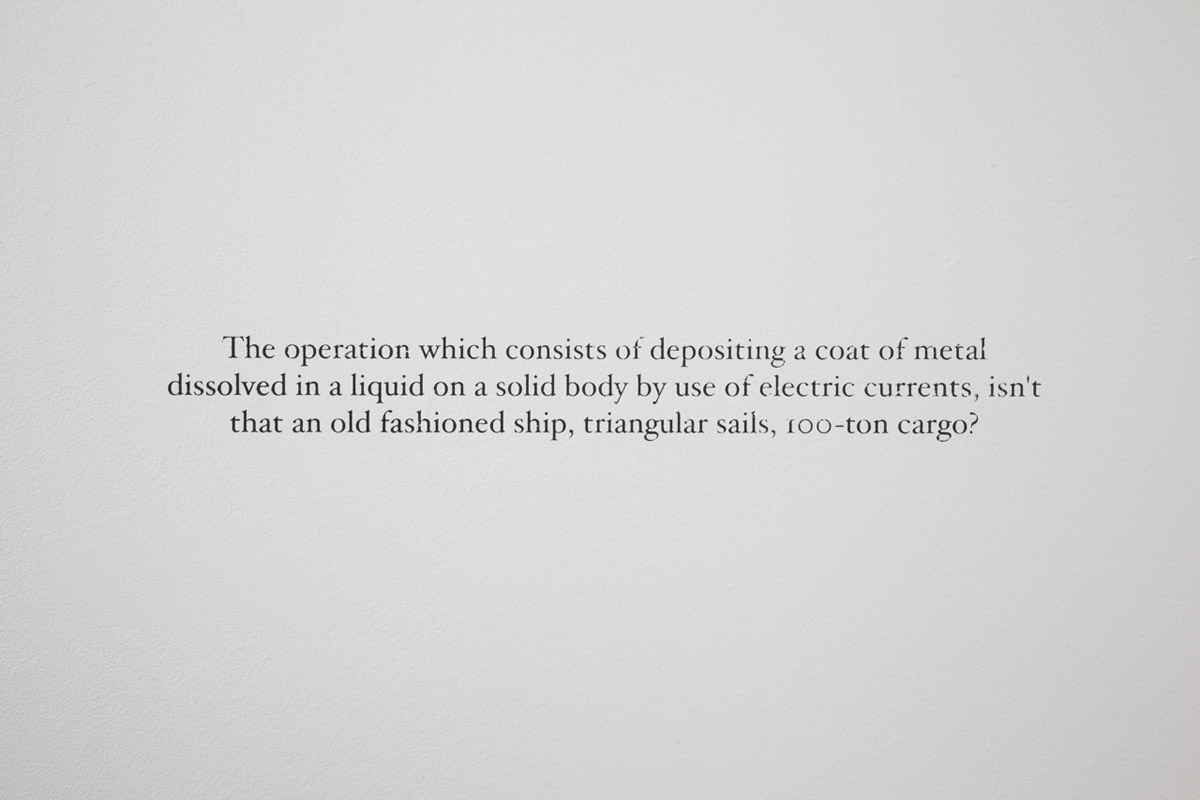

With a practice that includes photographs, found objects, text, video-projection and sculpture, Matt Sheridan Smith manipulates a variety of mediums to address notions of authorship, the readymade, originality, and value. Considering the value of artist’s labor, its relevance within a historical context, means of self-portraiture, and the precarious relationships between language, objects and representation, Smith employs ready-made, standardized or prescribed material to reveal the poetic effects of seemingly banal content, technologies, or conventions. As a platform for critical discourse, his practice is specifically designed for the fluid exchange of ideas between artist and viewer. In The Front Room, Smith presents a new suite of text paintings and sculptures derived from a game in Julio Cortazar’s 1963 novel Hopscotch, in which characters join the dictionary definitions of two homonyms using a conjunction such as “isn’t that.” Creating a false equivalence through proximity and a set of found poetry, these generative texts seek simultaneously to objectify the original word and force it to disappear in the face of its meaning. In presenting these texts—one from the novel and one by Smith—with a series of sculptural analogs and correspondences that give no indication as to which came first, Smith complicates the relationships between text and illustration, object and caption.