Since the 1970s, Lutz Bacher has developed a multi-faceted body of work that resists easy categorization. Rooted in a tradition of appropriation, she sifts through anonymous books, illustrations, pulp fiction, advertisements, self-help manuals, pornography, interviews, trade shows, and abandoned photographs. Making photocopies, hiring painters, shooting large-scale Polaroids, manipulating found TV footage, videotaping ambient walk- or drive-throughs, and always taking snapshots, Bacher searches for the noises that disfigure contemporary culture.

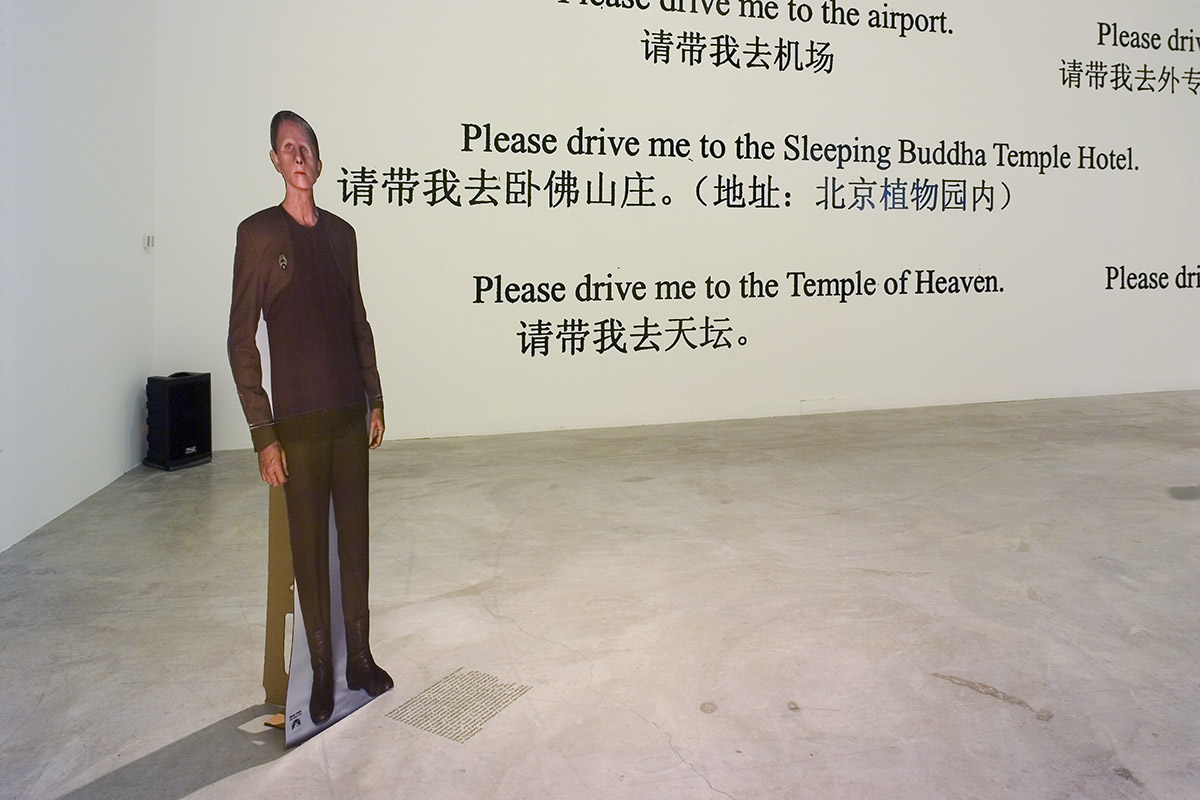

At the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, Bacher creates a site-specific installation that outlines her current artistic territory. The projection of a new, multi-channel video work, Our Beloved Revolutionary Sweetheart, dominates the Main Galleries and features an anthropomorphic line-drawing that moves over a pixilated, monochromatic landscape. A curved ramp intersects and dead-ends in the gallery space, debris of shattered electric guitars litter a corner, and life-sized cardboard cut-outs of Star Trek characters stand nearby. On a wall wheat-pasted with enlarged photocopies is a rotating display of past works by Bacher. Presented for periods of a few weeks, each grouping provides glimpses—although interrupted, provisional, and partial—of the artist’s overall practice. Among them are Bacher’s collage of documents: The Lee Harvey Oswald Interview (1976), a selection of her infamous Jokes (1985-1988); her Playboys paintings (1991-93); appropriations of Gap ads (Gap, 2003-06), her Polaroids of plastic trolls, Little People (2005); and Bien Hoa (2007), found photographs taken by an American soldier in Vietnam. Inspired by Anheuser-Busch’s headquarters in St. Louis, Bacher also fills a second space with stacks of Budweiser cases, which, along with an old Budweiser sign she collected years ago, threaten to transform the quiet gallery into a place of excessive intoxication. Outside, Bacher creates a sound installation triggered by motion sensors in the courtyard and covers the museum’s windows with a billboard-sized photograph.

Via sound, video glitches, alcohol, and the ongoing removal and replacement of artworks, viewers experience various types of interferences. Like a shape-shifting living organism, Spill resembles the mind of an artist at work more than it does a conventional museum exhibition. The accompanying publication SMOKE (Gets In Your Eyes), and published by Regency Arts Press, consists of photocopied photographs, letters, newspaper clippings, and email exchanges, and does not “catalogue” Bacher’s artwork but rather emphasizes the erratic gestures, juxtaposed references, comic punch-lines, and sudden gear-shifts that exist in the experience of the exhibition itself.