“The whole thing got weird the weekend before spring break,” Tim Portlock begins. He’s on the phone in Philadelphia, where his wife lives and where they cohabit during the summer. Portlock is a 2020 Great Rivers Biennial (GRB) award winner and the head of the undergraduate art program at Washington University in St. Louis. Before spring break his wife was visiting him and they had planned to fly back to Philadelphia. At this time the pandemic was gaining more people’s attention in the United States. They canceled their flight and drove to Philly. After Portlock drove back to St. Louis to resume spring break, “my first day was spent in all-day meetings.” Those meetings continued long after the university chose to close. “Right now, in June, we’re still running through different scenarios for the fall semester and what it might look like. Making contingencies if x or y happened. We’re hoping for a clearer picture of who is coming back, but knowing that once something is settled, things will change.”

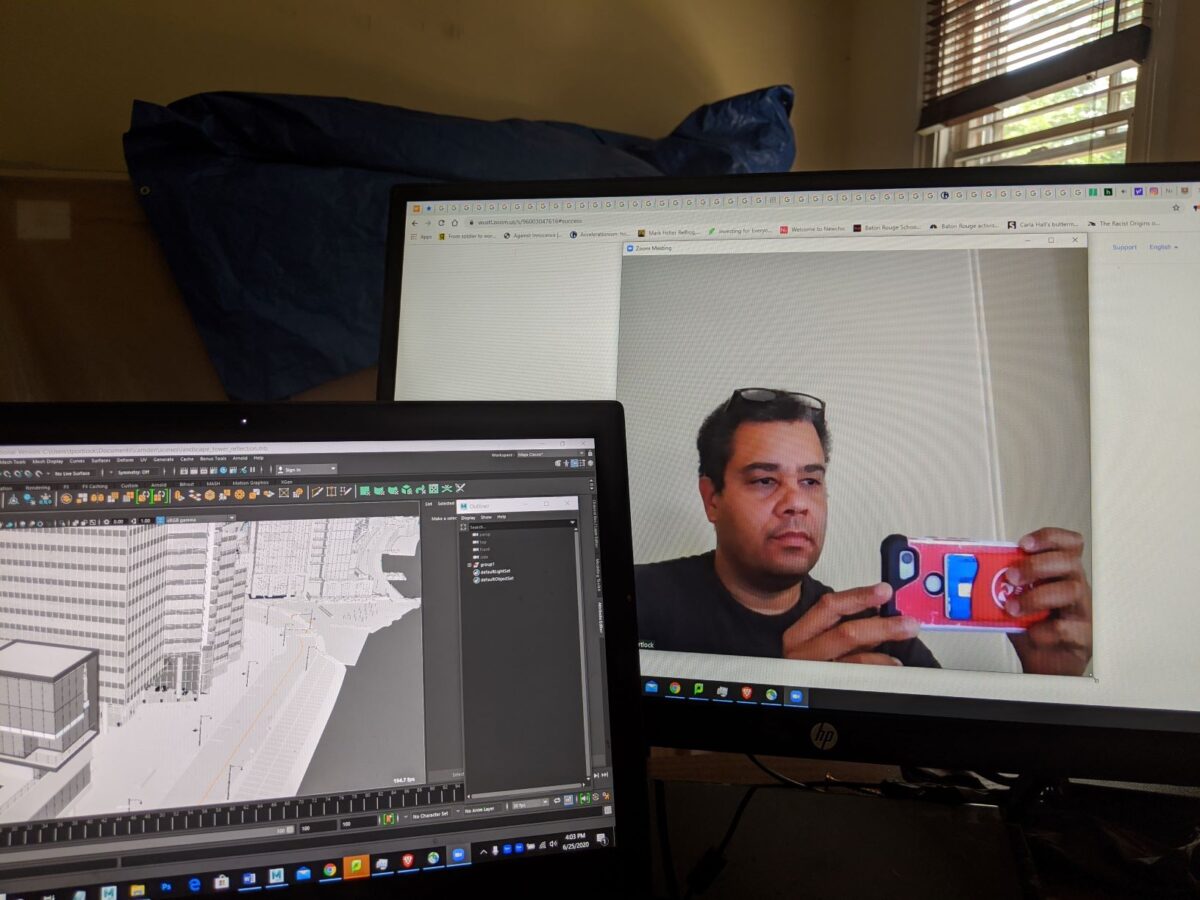

Amid all the Zoom meetings, Portlock says the art-making has gone “in crests and waves. I’m still working on stuff for the GRB show, [Nickels from Heaven], although the bulk of it is done.” Much of Portlock’s work, as he defines it, “is centered around a battle between optimism and decline,” a uniquely American battleground. “These two competing notions have always been there,” he says. His prints, most of which will be large-scale at CAM, show cities in decline, but “with the American sense of project at work.”

The concepts around his art are almost too relatable to our present moment. “How is progress defined? What makes the future better? What version of America is the better version? Some people try to imagine a better future, but it is terrifying to other people. Some people lack the imagination to see beyond what we have. Much of my work shows construction sites—a popular standard of progress is building, building bigger and more impressive things. But this doesn’t account for a lot of people’s experience, and this often plays out in protest. Not everyone’s experience is the same. Those who have been ignored are suddenly asserting the narrative.”

Portlock has made a series of works based on Las Vegas, which has its own special surreality, but many of his works, whether styled after specific cities or not, feel familiar—the grandeur of decay, the rot and rust of the past aligned with the shiny glow of the new, the absurd sparkle of the future.

“I used to go to different cities over the summer. For years nothing changed, then in 2104, there were dramatic changes—giant construction cranes everywhere. ‘Life is getting better,’ some people said. But that depends on your proximity to the buildings. How do they affect you?”

Portlock’s images are not tinged with nostalgia. The stories they tell are myriad, filled with competing notions of history. Portlock borrows the compositional conventions of American landscape painting of the 19th century—he is a former painter and muralist—operatic lighting effects, monumentality, the expansive horizon of the New World: a fertile, ripe land awaiting virtuous people to fulfill its destiny.

Portlock captures the crudeness and the exhaustion of that dream. “I think about older buildings as representative of a past way of life—those buildings built in the first half of the 20th century. Cities with big factories. They imagined social relations based on people walking to work or getting in a streetcar. Imagine buildings now. Who and what are they for?”

—Eddie Silva