CJ Mitchell introduces me to today’s virtual art class project, A Social Medium, based on the collage-work found in Kahlil Robert Irving’s exhibition At Dusk, which was part of the most recent Great Rivers Biennial. A Social Medium involves building collages based on the students’ own social media feeds, with the additional element of asking students what those feeds say about themselves, suggesting the possibilities of an allegorical self-portrait.

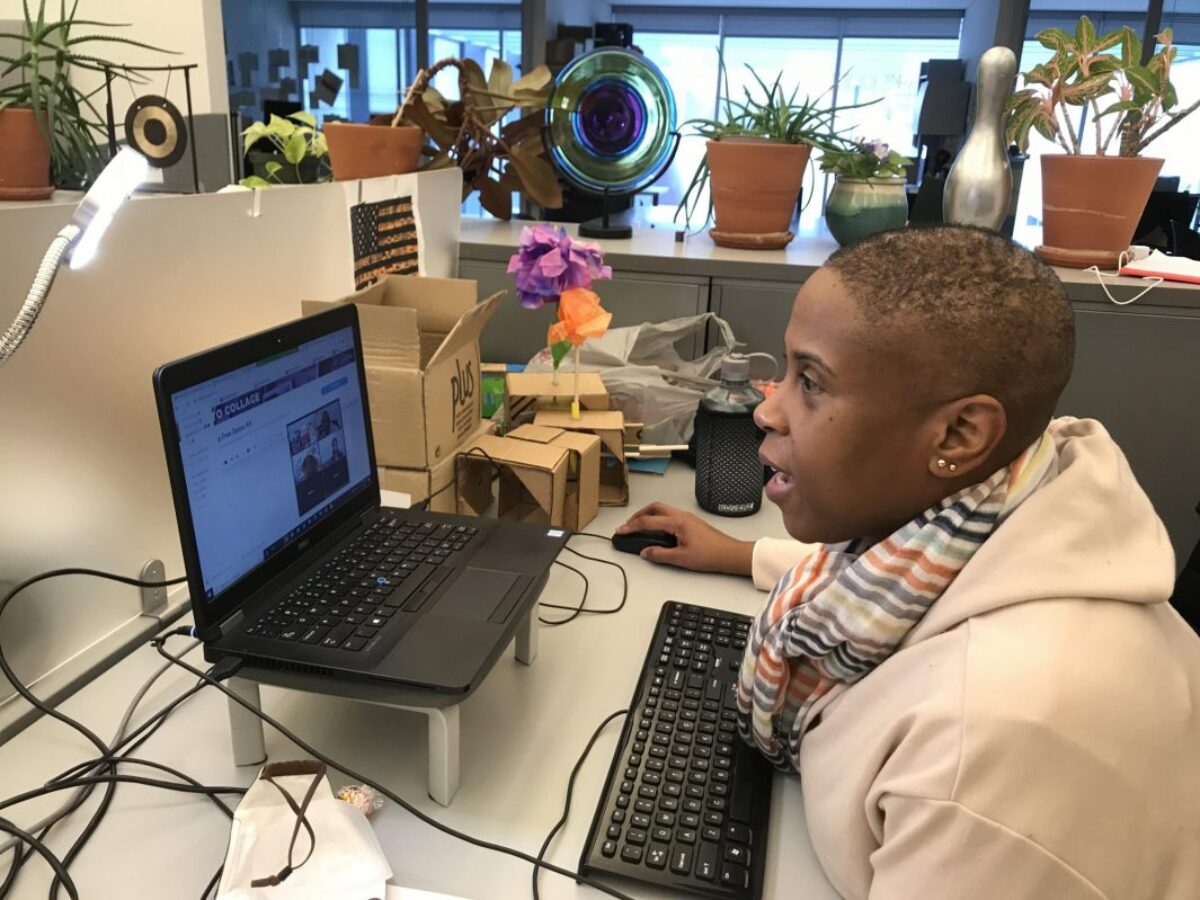

Today’s class is designated a Drop In Workshop as part of CAM’s ArtReach programs. CJ is dropping in on Metro Academic and Classical High School, better known as Metro High, but even though the school building is only blocks from the museum, the afternoon workshop is virtual. CJ is sitting at her computer in the museum staff office waiting for the Metro class to join her. She’s concerned about time, the class is only one hour, and that hour will pass quickly.

CJ is a veteran instructor and has taught in classrooms in London, New York City, and St. Louis, among others. She’s CAM’s Community Access Coordinator, which means she brings contemporary art education to groups throughout the St. Louis region, including schools and senior-serving organizations and living facilities. Like most teachers, she has been forced to adapt swiftly to the virtual classroom. “I still need to do a lot of demonstration, which can be a challenge because I’m not able to interact with individual students as readily as I can when I’m physically present. It’s easier to lose students virtually.

“I look directly into the screen and try to be as warm as I would be in the classroom. When teaching online It can be harder to get young people to show you what they’re working on, because they get so into making the art, not in the actual production. It takes more prompting to see what they’re doing. But online teaching does have its advantages: you have a captive audience and smaller groups.”

CJ takes time to go over her outline one more time to make sure the materials she wants to share are readily available on the computer. “Some student responses are beginning to show a weariness of the virtual is setting in,” she tells me.

We wait. Technical difficulties are happening on the other end of the line. The students begin to sign on and more than a dozen faces appear. CJ takes off her mask and introduces herself. She has one of the least teacherly voices I’ve ever heard from a teacher. Calm, comfortable, comforting, she sounds as if she’s taking her time even though she doesn’t have much time to take. She directs them to photocollage.com, which serves as their art-making tool, and demonstrates how to select a color background for their collages. They upload images and paste, with CJ reminding them to download the content and save.

CJ discusses repetition of images to form a pattern, and talks about Kahlil’s work, his large-scale vinyl collage is made up of hundreds of screenshot images, yet it’s not random. “A lot of forethought and attention went into what is seen,” she says. CJ introduces the element of symmetry, and how it may give a different design idea to a collage. “Think about music. The music you may be listening to is something you can reference in your work.”

Even though the students have been learning via Zoom for awhile, they’re still figuring out how to raise a hand, give a thumb’s up, or clap via chat—the new language of education through emojis.

After the class is over, I ask CJ about working with lifelong learners. She laughs. “Oh, there’s a lot more chatter with them.”

—Eddie Silva