Bharat Ajari has the kind of experiences you like to find in an art instructor: varied and intriguing. He has a Doctor of Ministry and Master of Divinity from Eden Theological Seminary, a Master of Arts in Professional Counseling from Lindenwood University. He is a poet and teaches creative writing and is involved in pastoral care, which is a non-denominational way of saying he helps and supports people in need. He’s also a visual artist, making paintings that look like vivid transformations of the physical world as it loosens its way toward abstraction.

I caught up with Ajari when he was teaching studio art in the eighth week of the third quarter at Vashon High School (a profile of Simiya Sudduth, who taught the quarter after Bharat, is coming soon). He has taught at the college level, in technical schools, and with people with learning disabilities, but this was his first time with high school students. Plus it was his first time teaching in the midst of “a year of disruption in their education.”

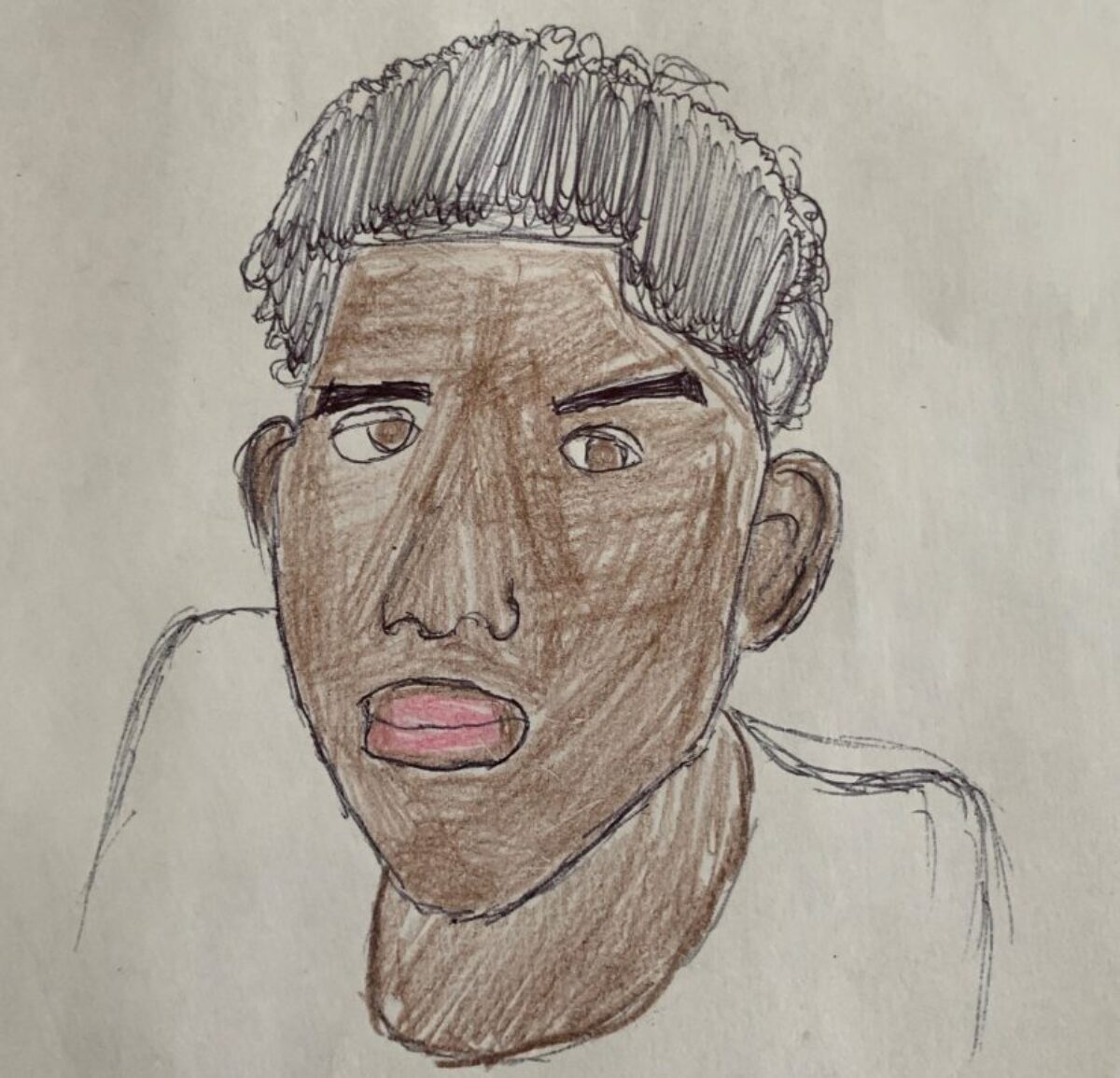

Like many teachers new to the virtual classroom, he changed his plans almost immediately. “We were going to create conceptual portraits of famous African Americans,” he says, with time and space given to research. But their past weeks and months of screen time didn’t lend itself well to the project. The pandemic has been a more inward-turning moment for teenagers as much as it has been for adults.

They moved to self-portraiture, with Ajari prompting the students with building blocks: What is a self? What does it mean to be African American? He wanted to get them “thinking seriously about being descendants of Africans and now speaking English.”

He gave the class time to adjust before introducing them to ideas like “concept” and “conceptual.” “I know what I look like,” he explained, “but what if I substitute triangles for eyes?”

“We did traditional representation with watercolor, then did other colors non-representationally. They are finding the power of deconstructing the self, then reconstructing from that new perspective. I’m not sure where we’ll be when we’re finished. But in the process they’ve been introduced to more African American artists than they’ve known before. And they’ve been through a process in which they re-envision and reimagine ‘what is a self?’ How to reimagine those things given the negativity they feel sometimes. They may gain visual tools with which to reconstruct themselves.”

“When I was a teenager, minority programs were geared toward math and science. In the creative writing spectrum at UMSL (University of Missouri–St. Louis) I got college credit and I was introduced to ideas. Reading the autobiography of Miles Davis changed my life. ‘Put art first!’ That is what I wanted to do the most.” Now he finds himself teaching teenagers at Vashon. “I wanted to open their minds to perspectives that I wasn’t able to get to until I was older.”

With a couple weeks left in the quarter, he reflects on where he and his students began. “Coming in, I quickly learned I had to slow down. I had grand designs for research, but I switched focus from studying someone else to studying the self. It’s more meaningful now. You’re actually struggling in the work to engage with a concept of the self. And I’m making work right alongside of them. This could be a graduate class.

“The heart of any educational endeavor is you have to be a believer—believe in what you’re teaching. Accessibility is the difference. Give kids the access, no telling where it goes.”

—Eddie Silva